Coach Education

Within a previous post on Observation, I highlighted the idea that coaches do not value formalized learning; Stoszkowski and Collins (2012) implied individual learning is substantiated through relatively familiar or realistic scenarios/environments. It’s for this reason that I question the current purpose of coach ed. programmes in the development of coaches; should current theoretical research not influence and reflect the itinerary and objectives for such programmes. From my experience, non-representative environments do not give coaches the opportunity to adapt and use knowledge acquired on an associated course within a controlled situation which they can then transfer into their club or athlete sessions.

As a coach, I use game based scenarios often in order to expand on instructions and explanations which then allow participants to have a better understanding of the application of a particular skill.

My question is:

Why if this is being taught to prospective coaches of how…

View original post 1,795 more words

Can Sports Coaching be Classed as a Profession?

Having recently been involved in a lecture looking to address the idea of professionalisation, questions were raised as to the use of the term ‘professionalisation’ and the context in which individual careers could fall under the banner of a ‘profession’. We discussed the idea of coaching as a profession, finding contrasting views into how this translates into the coaching framework and career pathway in comparison with other ‘professions’ leading us question whether coaching is a profession in itself.

The coaching profession vs. professional coaching

We felt that there is a lot of existing evidence that promotes coaching as a profession; however we also noted that in the sporting environment, many of the aspects discussed show the route into a professional status to be somewhat random with no clear structure or indication of what the coaching profession is, or the route you should take in order to reach a standardised ‘professional’ level of sports coaching. We related the term ‘profession’ to various characteristics, for example: the career being a main priority, acknowledged by others, long term training etc. whereas ‘professional’ tended to reflect a distinct image identified through approach, clothing, mannerisms etc. and with recognition of a role. This leads to a contrasting argument that sports coaching cannot be classified as a profession. If you look for example, at the voluntary coaches who make up the majority of coaches within the UK, these individuals take up their roles alongside full time careers and rarely continue to develop it as a sustaining career choice. However they present themselves and the club in a professional manner, reflect the club ethos and support player development. Therefore it could be suggested that the diversity of individuals involved in all aspects of coaching promote a professional image as opposed to addressing the role as a stand alone profession.

How does it compare internationally?

Looking at statistics given by Duffy et al. (2011) within ‘Sports Coaching as a ‘Profession’: Challenges and Future Directions’ which suggests international recognition of coaching in both a professional and voluntary context. 260,000 people are recorded as being involved in participation and performance related sport delivery in Germany on a full time basis, similarly Australia had a recorded 27,900 full time coaches with the USA classing 217,000 as full time coaches. In these instances full time coaching could be seen as a paid professional career. In comparison, UK statistics also show 36,537 individuals take up sports coaching roles on a full basis whilst a further 230,765 are recorded as part time. With the vast number of individuals taking up coaching on a voluntary or part time basis it is questionable whether the term ‘career professional’ and ‘sports coach’ can be used together.

Pathways to professional status

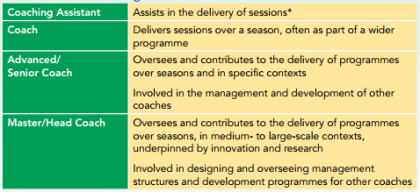

We noted the distinctive pathways available in careers such as medicine, teaching etc. in that there is a formalized structure to progress with clear development opportunities and increased responsibilities, alongside annual or monitored continuous professional development (CPD). Within coaching, structured progression opportunities are evident through the National Governing Body (NGB) coaching qualification framework and also via minimum operating standards workshops. However we questioned their practicality and application within clubs, specifically at grass roots level. For example those who receive level 1 awards are classified as ‘assistant coaches’. Within the guide given by the International Sport Coaching Framework (2012) – we are assuming each level (1, 2, 3 and 4) can be classified in relation to the image shown below – level 1 coaches should be supported by the coach (Level 2 or higher) in order to develop and progress their practice within a supportive environment in so emulating the coaching pathway. However, the guidelines related to coaching level and associated responsibilities may often be overlooked due to a need for coaches, meaning the development system is dependent on external factors and can vary from club to club and within different regions.

Coaching Framework – International Sports Coaching Framework (2012)

In other career fields you can clearly see when an individual has qualified as a professional but how is this recorded in sport? Professional football a great example of seeing ex professionals step into a coach or managerial role after retiring, often with little formalised coach education, experience or qualification. The subjectivity of appointments and ex players by-passing the development pathway is also a cause of uncertainty in suggesting coaching as a profession due to the randomised internal structure of high level performance roles.

Does coaching have professional education?

Whilst there is an obvious framework for coaches to develop in the NGB coach pathways, it became apparent that within sports coaching there is in fact more than 1 route into becoming a coaching ‘professional’ in the sense of acquiring knowledge and specific skill base. Professionals in medicine, law etc. have strict requirements of degree or postgraduate degree education; coaching allows individuals to choose various routes e.g. progressing through coaching awards and also taking coaching into further study through a degree programme. This can also be related to specific career pathways, for example when qualified, doctors become a clear member of a union showing they meet specific criteria in professional and applied abilities taught and emphasised within their years of professional education.

You could easily argue either (acquiring an NGB Level 3 or equivalent or the completion of degree qualification) gives an individual means to say they are professionals in their own right. However, the variation of experience etc. means there is no one way of comparing 2 individuals who class themselves as professionals via the same requirements. Due to this, measuring or specifying what makes a coach a ‘professional’ is very difficult to establish and filled with subjectivity. The level of experience an individual who takes the coaching award pathway would in general, be substantially greater than an individual who took coaching to degree level. It could however be argued that whilst a degree programme may, for its duration limit or reduce the applied experience of a coach; individuals are acquiring a vast arrange of theoretical knowledge and developing critical thinking and reflective skills that can be applied in practice.

Whilst each pathway provides knowledge and experiences:

- How many individuals who enroll onto degree programmes specialising in sports coaching or related courses do so with the intent of becoming a full time coach on graduating?

- How many coaches on the coaching pathway develop knowledge independently, seeking further experience and utilising education opportunities to develop?

Explicit ethical and value systems

We also explored the issue of a system which demonstrates and applies clear ethics and values. Within sports coaching, specific groups are often underrepresented such as women in football, though this is continuously developing, the vast number of women who actually participate in sport only a small percentage of coaches are actually women (Acosta and Carpenter 2006). Between 2000-2002 men received 9 out of 10 new head coaching jobs in women’s athletics (326 out of 361)(Acosta and Carpenter, 2002).

Whilst there is development in women taking lead roles within club structure, we questioned if professions should be able to distinguish male/female specific role as individuals should be equally knowledgeable for employment through following a set process of learning. Further discussion as to the core values and ethics surrounding sports coaching led us to the conclusion that whilst many professions ensure employment is continuously monitored and a widespread system is in place to ensure consistent professional standards such as signing the Hippocratic oath, within clubs, values and ethical guidelines vary from club to club with their ethos. Whilst there are workshops used to promote the values and ethics associated with Sports Coach UK and associated NGB’s, the workshops and content are very rarely enforced in a club environment as examples of good professional practice.

Again the question was raised that, if coaching is a profession why are there no enforced national/international guidelines that all who come under the banner of ‘coach’ must abide by and be actively monitored to ensure continuity of safe practice?

Differences in elite level sports coaching

Elite level sport provides distinct job titles across the board for those who support elite athlete development e.g. coach, nutritionist, psychologist, the list is endless. However in this context could we then argue that: Each role is a profession in itself? And therefore the sports coach is a professional? We found it difficult to distinguish the exact role of a sports coach within grass roots sport as more often than not the coaches also take up community development responsibilities if coaching within a paid capacity. Looking at the role from an elite perspective provides clarity and key responsibilities of the coach that could be related and compared to others within a similar environment.

Therefore after exploring each of the issues within this post, could you suggest coaching becomes a profession only in direct collaboration with related professions due to the diversity and uncertainty in specific practicing coach requirements ?

Laura and Andy.

References:

Abney, R. (2000). The Glass-Ceiling Effect and African American Women Coaches and Athletic Administrators, In: D. Brooks and R. Althouse, eds. (2000). Racism in College Athletics: The African American Athlete’s Experience. 2nd ed. Morgantown: Fitness Information Technology Publishers, 119-130.

Acosta, V.R. (1986). Minorities in Sport: Educational Opportunities Affect Representation. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance, 57(3), 52-55.

Duffy, P., Hartley, H., Bales, J., Chespo, M., Dick, F., Vardhan, D., Nordmann, L. and Curaab, J. (2011). Sports Coaching as a ‘Profession’: Challenges and Future Directions. International Journal of Coaching Science, 5(2), 93-123.

International Council for Coaching Excellence and the Association of Summer Olympic International Federations. International Sport Coaching Framework. [pdf]. Human Kinetics. Available at: <http://www.icce.ws/documents/2012/ISCF_1_aug_2012.pdf> [Accessed 9th October 2014].

Application and summary of topics discussed so far

Whilst the purpose of the blog was to reflect on my own coaching, I’ve found its uses were substantiated in the support it gave in research and extended learning opportunities as the year progressed. I think through this assignment, I’ve been able to cover a broad range of issues within coaching; however, I do have to acknowledge the purpose of the assignment may not have been fully met with regards to the evaluation of my own coaching sessions. In retrospect, the topics discussed reflect the diverse nature of sports coaching, I’m definitely happy learning from others, expanding my own knowledge base in order to improve my practice and in so developing my participants experiences.

In relation to my own coaching this year; I feel that it has been in a more supportive role, spending my time within clubs observing practices and becoming comfortable within the environment. For me, learning of others in a practical environment is invaluable. I have been able to apply theory into my coaching, using for example, anxiety strategies as highlighted within a previous post ‘Outline of key strategies for coping with anxiety ‘. Generally through applying such theories I’ve been able to approach my sessions and situations in which I may have previously avoided confidently. It’s been suggested that I can now apply and see the relationship theory has in the development of coaching as a profession, and I’m starting to view myself within and academic context as has been previously indicated by university tutors.

The blog has definitely pin pointed some of my characteristics or actions that in time I hope to find solutions too or improve through extra experience and further study. My interest in the theoretical side of coaching and how I can then use it to apply to and ‘educate’ others to use for the benefit of participants is actually really rewarding. In applying what I have learnt through my 2 years at UCLan and external coaching/teaching experiences, I think that my delivery and understanding of strategies and coach/player development has improved significantly.

I am beginning to understand how I work, and what I hope to achieve. This year has definitely taught me that things don’t always go to plan, and I think that this was part of what was holding me back; my reluctance to try new things due to fear of it going wrong or being judged, I wouldn’t say has completely disappeared, but has reduced somewhat. However, I also think this is what makes me as conscientious and hardworking as I am. I enjoy what I do. Both within the practical and theoretical side of coaching, I think there is much more that I could further investigate and then apply.

Part of my development will most definitely encompass further experience within various sporting situations; were available, I also hope to further my qualifications within different sports, looking towards official disability sport qualifications. I think many of the topics I have discussed throughout the blog, and possible future areas of interest could make a sound basis for further academic research, looking towards undergraduate and possible postgraduate dissertation.

Social Networking

The impact social networking now has on coach development is substantial. The range of information and communication with professionals that is now possible through sites such as twitter and through blogging tools provides both educational and practical opportunities for development.

For those seeking further understanding, learning from others and networking, the possibilities are endless. Accessibility associated with such means can influence a coaches understanding and application of resources and also acts as a method of seeking further clarification on those resources.

I’ve found that a lot of coach progression is about getting your name out there. Support available through social networks can help to do this. The purpose of this blog was to reflect on my own coaching practice, but I’ve found that it’s also helped me to develop interests and gain clarification through these sources.

It allows interaction with other professionals/ up-coming coaches who have experienced or are going through the same situations as yourself, learning from their mistakes and discussing possibilities for progression. It’s brilliant and something more and more people and businesses are using to liaise with colleagues/professionals. One of the benefits of such communication I feel, is to enable us to experience the emotions and thought processes generated through sessions by existing coaches. To put it simply, it’s easy. There are so many ways of interacting with others and putting your own thoughts out there. Current up to date information is there to be utilised and interpreted into individual sessions.

As suggested, this blog was initially started as part of my TL2133 module at UCLan; through it, I have been able to express my opinions and reflect on others practices. As this reflective process progressed through the year – following discussions with a tutor – I began to use twitter as a way of promoting a wider audience to read my blog, and gaining feedback from those who did which is a process supported by Dunlap and Lowenthal (2009) suggesting such networking improves the effectiveness of individual learning. The success of which has been reflected in the number of people I have had viewing and redistributing my posts.

I’ve found the use of social networking within a professional context to be really beneficial to my progression this year. I think part of coach development is about being open to new ideas, trying and reflecting on them and then allowing others to experience it, it’s something that is growing in popularity, and I think that it will ultimately play a key role in my own and future coach development.

References:

Dunlap, J. C. and Lowenthal, P. R., (2009). Tweeting the Night Away: Using Twitter to Enhance Social Presence. Journal of Information Systems Education, 20(2), pp. 129-135.

Thinking Outside the Box

I think there is a tendency amongst professionals to stick to what they know. For development purposes, using recognised structure promotes progression and focus whilst supporting and establishing confidence in the individual’s ability to coach. In some instances stepping away from traditional or well established structure can also be viewed negatively by peers, parents and spectators, due to a preconceived idea of what they expect from each session.

Traditional ideas make a firm basis for progression and can be seen as a way of developing athletes based on previous experience and success. Taking a risk to alter a training plan or approach sessions differently can be daunting for any coach; despite understanding of how such actions could positively influence participants the decision to change requires confidence and motivation to develop your own practice.

Coaches often show individual delivery styles often based on personal philosophy (Bennie and O’Connor, 2012), planning sessions to support personal objectives alongside ensuring progression of participants can be difficult ; I think some rely too much on what they have been taught and what they know works….after all if it works should it be changed?

At UCLan we’re pushed to go beyond our comfort zones, challenge tradition and try new ideas. This environment whilst controlled provides a stable platform in which to put into practice what we have learnt or observed within our role as both student and coach. However as suggested the environment in which this is possible is not always made available to existing professionals or volunteers within the sport; I think an environment in which to support and enhance learning by this method is paramount in creating and sustaining creativity and motivation in coaches. McLean and Mallet (2012) support this idea suggesting motivational factors for coaches can influence their approach to sessions and in so the progression of participants.

Reflecting how I have developed as a coach over the past year, I am beginning to stray away from the traditional ideas of coaching, thinking more to how I can develop athlete potential; leadership, teamwork, personal, and interpersonal skills are areas that I feel as coaches we can help to progress and in turn use sport to aid participants through their development. Altering my practice by changing how I structure my sessions seems an easy way to accomplish this; from experience, using repetitive drills demotivates participants slightly altering your approach and encouraging fun and interactive activities re-engages the learning process. If we can structure sessions in such a way that participants learn to develop their own thinking and understand strengths and weaknesses, we can then progress practices; harnessing ingenuity and using a semi-structured approach to sessions based on discussions with participants, coaches can create exciting a new activities.

I’m not saying to completely disregard the structure learnt through coaching courses, they work for a reason; I think from experience changing sessions and being creative not only motivates participants, but puts the drive back into coaching. The monotony of delivering the same sessions and planning to a predetermined structure can sometimes make us question the reasons for going into coaching; generally it’s for this reason that thinking outside the box can benefit not only the participants, but coaches, parents and spectators. It’s something that needs to be more acceptable; trusting coaches to experiment with activities and allow them to reflect on the success or failure of such activities; challenging tradition is essential in progressing sport for the better. Each development in the coaching process has been accomplished through trial and error and I think it is something that needs to be supported through the learning process.

References:

Bennie, A. and O’Connor, D., (2012). Perceptions and Strategies of Effective Coaching Leadership: A Qualitative Investigation of Professional Coaches and Players. International Journal of Sport and Health Science, 10, pp. 82-89.

McLean, K. N. and Mallet, C. J., (2012). What motivates the motivators? An examination of sports coaches. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 17(1), pp. 21-35.

‘It’s all about the kids’

The title surmises the basic premise that grassroots coaching is made from.

Many coaches will begin their careers working with development groups; beginners, often children and within single sports dismissing basic skills in order to focus on those directly associated to the activity. However, as Logan et al. (2011) identifies fundamental movement skills (FMS) need to be first taught, practiced and supported throughout in order to enhance skill acquisition. If we were to ask participants what they want from sessions, from experience, they will instinctively begin to list skills associated with the sport. Most start participating in sports due to role models through television, family or peer involvement and for this reason a preconceived idea of what sport involves is already ingrained into their ideas of what they hope to achieve.

Agility, Balance and Co-ordination (ABC) skills are often placed under the umbrella term of FMS. As coaches understanding the basic building blocks that influence future performance within multiple disciplines (Hands, 2012) I feel is paramount in the development of participants.

I have had the opportunity to not only take part in but lead FMS workshops, delivering a series of possible sessions, and educating young leaders in the importance of such skills. The availability of courses to enhance coach awareness of the impact acquiring such basic movement patterns has on future development could in turn help to progress children’s learning of new skills. As suggested, children acquiring such skills at an early age influence how they perceive and succeed at increasingly complex skills.

Through attending a recent ‘Introduction FUNdamentals of Movement’ course; being the only second year, it was interesting to see how first year students viewed the importance of fundamentals and actually, how much they knew. Whilst I found the general understanding of the principles of FMS on average was good, being able to apply them within sessions seemed slightly more difficult and I think that this would transfer into club or community sessions.

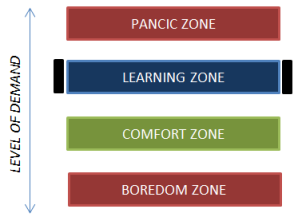

Within the FUNdamentals course we were presented with a series of diagrams to support the learning and application process.

For me I think the ‘comfort zone’ reflects a state of mind for both coach and athlete, within this zone none or very little learning occurs. Tendencies to stick to what we know and become complacent in the learning and development process is something that through greater understanding of FUNdamentals and associated skill/activities could be improved.

As coaches we want participants to be in the ‘learning zone’ it is here that development takes place, participants need challenges to achieve to and strive towards, promoting a growth mindset. Whilst I think it’s important for participants to progress at their own rate and make judgements based upon previous experience, current skill level, and how they view a task, I also understand the possible reluctance of learning new skills and the ability to use FMS to base both existing and new skills is an aspect of coaching that I feel needs to be addressed. Making skills relatable and using participants’ previous experience to support the learning process is one way of accomplishing this.

LTAD model

This idea of promoting ‘Physical Literacy’ in the early years of participation as a structure for Long term Athlete Development (LTAD) as suggested through the course isn’t something that I generally see or have experienced much in coaching courses. However, workshops such as ‘An Introduction to the FUNdamentals of Movement’ provide a firm basis for coaches to understand and apply. Much of the reasoning behind FUNdamentals is to create an impressionable and lasting experience that influences future participation in sport (Foreman and Bradshaw, 2011).

The LTAD model proposed here, highlights just one stage (6-8 years) as the focus on FUNdamentals; however as suggested in the workshop book, this is progressed through to the latter stages and can act as a way of regressing skills in order to improve.

It was suggested to follow a process similar to S.T.E.P.S –referred to in previous posts – to adapt and progress activities, allowing participants to indicate their awareness of environments and situations posed by the activities.

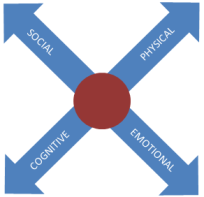

The spec model was used to explain the various aspects needed to design a successful session or activity in relation to the FUNdamentals. Part of the spec model signifies the multidimensional process coaches must go through when reflecting on their sessions in order to progress or regress at appropriate levels and in relation pitching the activity at the right skill level.

Part of what Sergio (the tutor) was having us think about and question through the activities was:

‘Are you challenging all aspects of the spec model?’

The question itself provided the first years in particular with a directed thought process when delivering, observing and then reflecting on theirs and other sessions. This process is vital in ensuring sessions are beneficial to participants; developing THEIR self-awareness for how their body adapts to various activities, understanding areas such as counter-balancing and how to manipulate their body to achieve tasks.

I think the delivery and interactive nature of the workshop made everyone think how they could successfully apply the content into their own sessions. Looking at developing my own coaching, regardless of previous awareness of FUNdamentals, I’m now more comfortable in implementing it into my sessions, knowing how to progress skills and break them down in order for participants to learn.

References:

Hands, B., (2012). How fundamental are fundamental movement skills?. ACHPER Active & Health Magazine, 19(1), pp. 14-17.

Foreman, G. and Bradshaw, A., (2011). An Introduction to the FUNdamentals of Movement. Coachwise: Armley.

Logan, S. W., Robinson, L. E., Wilson, A. E. and Lucas, W. A., (2011). Getting the fundamentals of movement: a meta-analysis of the effectiveness of motor skill interventions in children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(30), pp. 305-315.

FUN or COMPETITION

Brian McCormick highlights the differing opinion of coaches with regards to enjoyment of sports sessions.

Surely enjoyment and participants having fun whilst benefiting for the training should then aid in their competitive accomplishments. This age is a crucial and influential factor for later sports participation. One bad experience can mean minimal structured physical activity.

Thinking about athletes taking that step to progress their development within the sport should be down to personal preference, the rest I think should be using sport as an enjoyable way of promoting physical activity and to allow children to socialise and experience new things within a safe and structured environment.

When I think about my own coaching, I try and have participants having fun through training, yes there are times where I need them to focus and listen to what I am telling them, but looking towards competition I find they’re a lot more receptive when explaining progressions or further areas to focus on. I think the coach athlete relationship that I have referred to previously is really important in providing an enjoyable, motivating and progressive environment….

FA talent development…rethinking your practice

Recently, Nick Levett FA national development manager for Youth Football discussed developments in the FA approach to youth participation and grassroots sport. The lecture was part of our TL2072 Talent pathways module, closely relating to an upcoming assignment.

Going away from the actual purpose and relation the lecture had to modules; one of the biggest things I took from the lecture was a comment Nick made:

“Don’t forget why you do the job that you do – helping kids fall in love with sport”

This is so important and something that sometimes I feel coaches overlook. We get into a routine and plan to what is expected of us. I think everyone has a reason for beginning to coach; coaching children and grassroots sport for me needs a completely different approach and delivery style. Thinking about reasons for participation and how you as a coach can impact the development of individuals should in theory improve your practice.

So ….in a previous post I discussed the changes imposed by the FA and links between Extrinsic Motivation and Youth Sport; Nick emphasised the purpose of grassroots participation, referring not to the trophies and recognition but to the lasting impact coaches have on participation. Understanding how a good experience in sport can influence later participation (Kirk, 2005) is again overlooked; I think we – especially in relation to grassroots – concentrate more on the now than the future. If we’re looking to encourage participation in sport regardless of limiting factors such as age and disability, first and foremost it needs to be enjoyable.

The FA has recently changed their stance on how they approach competition for grass roots participation; their aim is to have more children participating in football, improving through fun and age relevant activities and competition. I’ve found kids love competition, they thrive on it, having the ability to focus in order to achieve and show willingness to learn from mistakes. However whilst, and as shown competition can play a positive role in the development of athletes I think sometimes it can be used as a way of filling time and having a way of producing and showing results to justify money spent. I think it’s true to say adult’s value external reward more than the participants themselves.

“Our challenge as coaches is to never demotivate children”

Sometimes I think that coaches can become entangled in the success and publicity side of competition. We rarely challenge the purpose of the competition or the impact it has of children’s development. Competitions can also emphasise differences in skill level and potentially side-line less able participants in order to secure a positive result. We need to think of a way of providing equal and opportunistic competition that harnesses children’s excitement and drive whilst maintaining their enjoyment of participation; providing inclusive sessions/games that allow all participants the same chances to develop self and game awareness could influence future performance but also lay a good foundation for further participation.

“Never be that coach that is the reason a kid stops playing sport…if you are, you’ve failed”

Listening to those who participate in grass roots sport, taking the time to acknowledge their understanding and their needs from the activity are all important factors in progressing sport for the better. I think younger participants often have a better understanding and application of skills/tactics then as adults we give them credit for. I’ve previously indicated that I felt my role as a coach was as an ‘expert’, I’d been trained to deliver and teach skills and to help- participants to progress using a set method of instruction set by NGBs.

Through the lecture, Nick explained a series of answers given by children during research by the FA about reasons for participation. When we were asked, there were some answers such as ‘Important I win trophies and medals’ that were suggested as possible answers, NOT ONE participating child in 55 groups had picked that answer. Again I think this shows that what we perceive as of importance to child participation and enjoyment in regular sport is incorrect, and also supports the purpose of gaining understanding of participant opinion and purpose for participating in sport. Preferred responses such as ‘I like meeting new friends’ and the top answer of ‘Trying my hardest is more important than winning’ show the social aspect of participation is valued by children much higher than winning.

I think as coaches we need to step back, review the situation and find ways to change. Make it simple and go back to the basics of each sport; as adults we often overcomplicate situations, discussing changes or potential differences in practice with the participants is just one way to combat this. Kids and adults view sport very differently, and I think it’s important to distinguish what exactly children want to achieve from sport in order to provide appropriate environments to play.

Through research, the FA has developed child friendly football. When Nick was explaining the structure of youth participation and relating it to previous models he referred to a process of reflection in which they needed to discuss what was good, what was bad, and what needed to be changed. Whilst it was also suggested that we should look and analyse other countries and NGBs Nick enforced that we should not copy their systems; differences in approaches can be controlled by culture, weather systems and facilities which cannot or would be difficult to replicate in Great Britain.

When describing developments in the structure of youth sport, Nick talked about changing the playing size, number of players and reducing the ball size in relation to specific age groups. Much of what was said is relatable to the S.T.E.P.S process.

Space

Time

Equipment

People

Speed

Each of the changes imposed by the FA help to create opportunity for participation, development of skill and tactical awareness. As suggested, these changes could be challenged by coaches, parents etc. due to a lack of understanding of the benefits to overall performance and participation factors.

How easy is it for coaches to implement this?

It was interesting throughout the lecture and after; as developing coaches, most of us agreed with what Nick had said and understood the reasons and justifications for what he had explained in relation to developing sport for the better BUT….as coaches we are also expected to respect the structure and running of clubs that we participate/volunteer in. I think it’s natural to –when planning an event –think of the extrinsic factors such as trophies and medals. after all that’s what we’ve grown up with. More and more, I am seeing events finishing in participation certificates as opposed to solely providing clubs/individuals who have placed medals etc. I think that this enforces the importance of participation and allows all to leave with a sence of accomplishment regardless of result. Part of progressing sport is about reviewing existing weaknesses and finding ways to change them, it is something that as a student I am seeing more often but is not something all NGBs appear to be utilising. Maybe it’s a case of being scared of change and accepting flaws in the structure, sport, and particularly as a profession is constantly evolving; using the experience of coaches and feedback from participants could improve all aspects of sport and influence individuals.

I think the change in the FAs approach to youth sport shows the progression of sport as a whole and a change in focus from result to enjoyment and development.

References:

Kirk, D., (2005). Physical Education, Youth Sport and Lifelong Participation: The Importance of Early Learning Experiences. European Physical Education Review, 11(3), pp. 239-255.

As a coach, do you understand why athletes experience burnout in sport?

Here, I’m looking at competitive sport; athletes participating at varying levels, performing alongside others and training to achieve a goal.

Young athletes participating in sport may appear to become disinterested and exhausted by the thought of training with little obvious sign. It’s something that as coaches we will all experience and is an inevitable problem when working with junior athletes; at this stage, participants are developing personal interests, making their own decisions and incorporating their social life into their day to day routine. It’s due to the diverse and individual nature of each participant that coaches may find it difficult to distinguish and identify potential dropout (Dale and Weinberg, 1990).

Smoll and Smith (2006) reflect the relationship a coach has when working closely with athletes; looking closely at the influential factors those athletes may replicate from coaches and the trust they place their training and progression.

As a coach, I’ve previously worked with a swimmer who joined a local swim club aged 8, by 11 it was felt her development was being impeded by club structure and coach experience. She moved to her present club and seemed to flourish and progress through her training. By 15 she lost all motivation for swimming; she felt the passion for the sport had gone, she no longer wanted to be at the pool for 5:45am, spend each evening at land training and in the pool and miss parties for competitions but she still did it. I think a big factor in this may have been both injury and subsequent lack of county and regional qualifying times that had been emphasised as an achievable target since beginning at the club.

Something we’ve discussed within a lecture and I’ve researched further emphasises the impact family can have on athletic and talent development.

Further discussion approached the influence her family had on swimming; the hours spent driving to training and competitions, the financial aspect and lack of obvious competitive progression led her to feel like she had let down those who supported her.

This shows the pressure that young athletes place themselves in. I say place ‘themselves’ as I think there is an element of athletes thinking it is their responsibility to perform and reflect the effort that their ‘support team’

Similarly, we saw in the 2012 Olympics elite athletes feeling increased pressure not only to perform for their coach, but to show GB that the money and hours spent to train were having an impact on the development and success of the sport. Those who did not achieve felt that they had let those who supported them down. Excessive pressure from coaches, parents other can lead to a feeling of failure and not meeting expectation.

In the context of the swimmer, Hill (2013); Cresswell & Eklund (2006), suggest athletes who express and feel a sense of commitment to train whilst lacking motivation experience burnout, similarly Gould (1993) implies burnout as the excessive stress a performer places on themselves to perform in competition.

Raedeke & Smith, (2001):

1) a sense of reduced accomplishment in terms of sport skills and abilities

2) emotional and physical exhaustion associated with practice and competition

3) devaluation of participation and performance in sport

Dale and Weinberg, (1990):

1) Exhaustion

- A loss of concern, energy, interest and TRUST

1) Negative change in an individual’s response to others

2) Attitude towards what they have or will accomplish changes

- Feeling of low personal accomplishment = low feelings of self-esteem, failure and depression

3) LONG PROCESS WHICH OCCURS OVER TIME

As indicated, I feel that injury played a big part in burnout for this athlete; her progression through the sport was halted in order to receive treatment and go through a rehabilitation process – this was also followed by further injury – that ultimately resulted in an obvious decrease in fitness in comparison to her peers. She could see those in her social group and of similar ability achieving county and midland times. Following this, the amount of effort and focus she placed on training was substantially reduced; it’s a knock on effect that meant her development remained at the same level. Her personal feelings towards training left her contemplating her future in the sport, her social life suffered as she felt their ability and experience was surpassing her own, and her relationship with the coach was significantly affected.

What I’m trying to put across is that as coaches we are not educated in the way our athletes experience sport, we’re taught how to deliver sessions; as a developing and progressive coach I think that we do not consider burnout in athletes and its possible effect on future participation in physical activity. The research is there to support coaches to understand the varying factors that could influence the motivation and progression of performers, however the knowledge and understanding isn’t.

A recent TL2133 practical was to allow coaches to focus on individuals challenges and perceptions of the activity, delivering a small session to 2 of our peers…maybe it’s for this reason (size) that coaches often do not have time or feel confident to approach possible problems for individuals within their coaching sessions. Following the session, I discussed its importance with Cliff and supported the idea that as coaches we often overlook working on a one-to-one basis. Ultimately this interaction should allow coaches to understand how the athlete approaches tasks.

The problems the swimmer was experiencing was highlighted by her head coach; they worked together to set and smaller and more achievable targets and in turn this has led to her participation and enjoyment increasing. Through the work and interaction with her coach she is now finding that she is motivated to train to improve.

References:

Cresswell, S.L. and Eklund, R.C. (2006). Athlete burnout: Conceptual confusion, current research and future research directions. In: S. Hanton and S. D. Mellalieu., Eds., Literature reviews in sport psychology. New York: Nova Science. pp. 91–126.

Dale, J. and Weinberg, R., (1990). Burnout in sport: A review and critique. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 2(1), pp. 67-83.

Gould, D. (1993). Intensive sport participation and the prepubescent athletes: Competitive stress and burnout. In B.R. Cahill and A. J. Pearl., Eds. Intensive participation in children’s sport. Champaign: Human Kinetics. pp. 19-38.

Hill, A. P., (2013). Perfectionism and Burnout in Junior Soccer Players: A Test of the 2 x 2 Model of Dispositional Perfectionism. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 35(1), pp. 18-29.

Raedeke, T.D. and Smith, A.L., (2001). Development and preliminary validation of an athlete burnout measure. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 23(4), pp. 281–306.

Smoll, F. L. and Smith, R. E., (2006) Leadership Behaviours in Sport: A Theoretical Model and Research Paradigm. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 19(18), pp. 1522-1551.

Coach Education

Within a previous post on Observation, I highlighted the idea that coaches do not value formalized learning; Stoszkowski and Collins (2012) implied individual learning is substantiated through relatively familiar or realistic scenarios/environments. It’s for this reason that I question the current purpose of coach ed. programmes in the development of coaches; should current theoretical research not influence and reflect the itinerary and objectives for such programmes. From my experience, non-representative environments do not give coaches the opportunity to adapt and use knowledge acquired on an associated course within a controlled situation which they can then transfer into their club or athlete sessions.

As a coach, I use game based scenarios often in order to expand on instructions and explanations which then allow participants to have a better understanding of the application of a particular skill.

My question is:

Why if this is being taught to prospective coaches of how to improve understanding both technically and tactically for participants is it not being emphasised and supports in the delivery of coach education programmes.

It is the solving of problems and challenges that improve a coach’s knowledge and delivery approach and I feel that this can only be improved within realistic and opportunistic settings, which are not currently being met.

Similarly to a previous post on Learning Styles, Gilbert and Trudel (2005) have suggested like kinaesthetic learners, knowledge for coaches is supported through practical application resulting in better understanding and adaptation in future. Stoszkowski and Collins (2012, p.3) suggest that ‘formal coach education may still have a vital role to play in the professionalisation agenda’. I agree with this, the conformity that NGBs require from their coaches is essential in creating a professional and well-designed delivery programme/structure for participants to benefit from. However Nelson and Cushion (2006) – along with various other academics – have incorporated the idea that each coach will bring with them personal experience which will influence their thoughts and interpretation of various coaching scenarios. I think for this reason their needs to be some kind of reform on the way all NGBs deliver their coaching programmes; whilst current assessment on courses require coaches to follow a distinct pattern, most (including assessors) know that this is not always possible and often an impractical and time consuming approach to sessions.

Piggott (2012) summerises existing literature associated with formalised coach education implying NGBs have a preconception of both the coach and participants which is reflected in the delivery of associated courses. It is becoming more well known amongst academics that formal coach education plays only a minor role in the development of coaches (Gilbert et al. 2006).

In terms of observation as an integral part of coach development; Taylor (1992) suggests that observation and contextual learning will result in a lesser degree of negative experiences experienced by the coach. The idea that coaches are influenced within their development through social interaction (Stoszkowski and Collins, 2012) is something that I did have knowledge of but through reading the ‘Communities of Practice, social learning and networks: exploiting the social side of coach development’ article has developed a better understanding into the possible negative implications of observation. Whilst I suggested that it is important to observe and witness both positive and negative coaching methods, I agree with Stoszkowski and Collins’ idea that coaches – especially novice – will aim to replicate coaching behaviour and procedure, and may in fact not understand and be able to reflect on good or poor practice. Having recently discussed this element of observation, it has lead me to question what exactly the prospective coach would be observing, the coach or participants. My initial answer was the coach, but then from that you could also imply the participants’ development and enjoyment could indicate good or bad practice; I’m a firm believer that observation can play a crucial factor in professional development and that it should be used and incorporated into training practices, if not just to highlight the importance of taking the time to observe others in a familiar environment to your own in order to develop your own practice.

Currently sports qualifications set down by the associated NGB (and often in conjunction with UKCC) do provide an indication and are aimed at specific roles with a club, e.g. level 1 assistant coach; however as indicated previously and in relation to Stoszkowski and Collins (2012), there is little actual and realistic application to sports coaching, instead NGBs opt for a formalised training system in which they deliver a series modules often over 2-3 days culminating in a 10-15 minute delivery by participants to peers in order to pass. I don’t think that these experiences – and in fact my own experience of delivering a ‘session’ lasting less than 15 minutes to a group of 4 of my peers – is a sufficient way of assessing eligibility to coach having followed a set structure through the assessment.

Recently there was a discussion over the purpose of the initial day of level 1’s where the primary aim is to learn about the purpose of coaching, and the warm-up phase of a session. It was suggested that similar to the recent development in Criminal Record Bureau (CRB), there should be a generic one day course focusing on these elements that can be done in conjunction with any NGB or Coach Ed. Provider in order to provide more time to give developmental ideas and progressions for activities, but to also allow coaches the experience of delivering full sessions (Intro, Warm-up, Main and Cool-down/plenary) as for many, the first time they deliver such sessions will be with a full group of participants. It is also interesting to hear that many of the coach educators do not agree with the purpose of certain modules on related courses. As indicated, currently there is minimal opportunity to experience coaching practice with the support of the NGB/training provider in order to implement strategies and knowledge acquired on a coach ed. Course (Nelson and Cushion, 2006)

I initially suggested that I ‘willingly’ take up opportunities of observation and it seems that research is correct in suggesting that those who take their own initiative in seeking further clarification benefit; from this, Werthner and Trudel (2006) indicate that individuals who seek further opportunity and experience in order to maximize personal and professional development should not be directly related to formalized coach education or informal and unplanned situations.

An interesting strategy to promote collaborative learning by Kilty (2006) that also supports my suggestion that observation could aid development, involves what I can only refer to as restructuring the typical hierarchy within coaching; she proposes incorporating co-head coach models, Arnone and Stumpf (2010, P.17) reflect that ‘Successful co-heads developed a clear understanding of their distinct roles and Responsibilities’ which I feel would ultimately support what the NGBs are wanting to achieve through their coach ed programmes. Other strategies Kilty (2006) suggests are to encourage questioning from coaches and promote observation and reflection of others practices.

Within the development of coach education there is the possibly of peer mentoring and support – similar to that on Post Graduate Certificate in Education (PGCE) courses – available to coaches through coach education as Bloom, Durand-Bush, Schinke, and Salmela (1998) recognise the positive development of coaches using such strategies. There are various elements as highlighted by Vargas-Tonsing (2007); Allen and Howe (1998) that stipulate the areas in which professionals feel should be adopted by NGBs, examples of these are: communicating with parents, athlete awareness (motivation, anxiety), building character. They do however also state the value existing coaches’ place on extrinsic motivational factors of such courses i.e. certification; supporting this, Nelson and Cushion (2006) suggest imply the responsibility for adapting programmes – content, structure, delivery, and outcomes – is ultimately the responsibility of the NGB/provider.

Stoszkowski and Collins (2012, p.8) reflect the benefit that observing, interaction and communication with peers can have on developing coaches but they limit this to those with a ‘clear vision’ from a ‘philosophical standpoint’; it is at this point as previously, that the question of who gages whether an individual has the right depth of understanding in order to make use of such experiences within their development? There are 3 areas of reflection suggested by Gilbert and Trudel (2001) which indicates the importance of in context experiences: Reflection-in-action, Reflection-on-action and retrospective reflection-on-action is it not therefore more appropriate to take opportunities to witness different strategies and how individual coaching philosophies regardless of the stage of the participant?

Much of this blog is an aspect of my learning and development through sport, it promotes reflection through observation and personal experience. I appreciate that each NGB has different goals and criteria for their coaches; however there does seem to be a change in a coach’s approach, which is reflected in our degree. I think NGBs need to be realistic about what happens within their sports at club level and adopt a different approach in order for prospective coaches to be ready to deliver sessions that meet their expectations. Through reading various literature, I think that coach education will still play a major role in coach development and the delivery of sport to the wider population, as Stoszkowski and Collins (2012) suggest, I think that this must be a culmination of various strategies that promote vocational learning whilst providing structure and controlled learning experiences.

There seems to be a general consensus that coach education courses do not provide all the necessary elements that a coach should learn prior to planning and delivering sport-specific sessions, how the providers use this information to improve the quality of the courses is somewhat unknown though there does seem to be some development shown in some NGBs focusing on the less traditional objectives i.e. Fundamentals which then reflects in the structure and ultimately knowledge gained.

References:

Allen, J.B. and Howe, B.L., (1998). Player Ability, Coach Feedback, and Female Adolescent Athletes’ Perceived Competence and Satisfaction, Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(3), pp. 280-299.

Arnone, M. and Stumpf, S. A., (2010). Shared leadership: from rivals to co-CEOs. Strategy and Leadership, 38(2), pp. 15-21.

Bloom, G.A., Durand-Bush, N., Schinke, R.J. and Salmela, J.H., (1998). The importance of mentoring in the development of coaches and athletes. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 29, 267-281.

Gilbert, W., Cote, J. and Mallett, C., (2006) Developmental paths and activities of successful sports Coaches, International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 1(1), pp. 69-76.

Gilbert, W. D. and Trudel, P., (2005), Learning to coach through experience: conditions that influence reflection, Physical Educator, 62(1), pp. 32-43.

Gilbert, W., & Trudel, P., (2001). Learning to coach through experience: Reflection in model youth sport coaches. Journal of Teaching and Physical Education, 21, pp. 16-34.

Kilty, K., (2006), Women in Coaching, The sport Psychologist, 20(2), pp. 222-234.

Nelson, L. J. and Cushion, C. J., (2006). Reflection in Coach Education: The Case of the National Governing Body Coaching Certificate. The Sport Psychologist, 20(2), pp. 174-183.

Piggott, D., (2012). Coaches’ experiences of formal coach education: a critical sociological investigation. Sport, Education and Society, 17(4), pp. 535-554

Stoszkowski, J. and Collins, D., (2012). Communities of Practice, social learning and networks: exploiting the social side of coach development. Sport, Education and Society, pp. 1-16.

Taylor, J., (1992). Placing Demands on Young Athletes In: T. M. Vargas-Tonsing, (2007), Coaches’ Preferences for Continuing Coaching Education, International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 2(1), pp. 25-35.

Vargas-Tonsing, T. M., (2007). Coaches’ Preferences for Continuing Coaching Education, International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 2(1), pp. 25-35.

Werthner, P. and Trudel, P., (2006). A New Theoretical Perspective for Understanding How Coached Learn to Coach. The Sport Psychologist, 20, pp. 198-212.